Fields of Recovery

2025

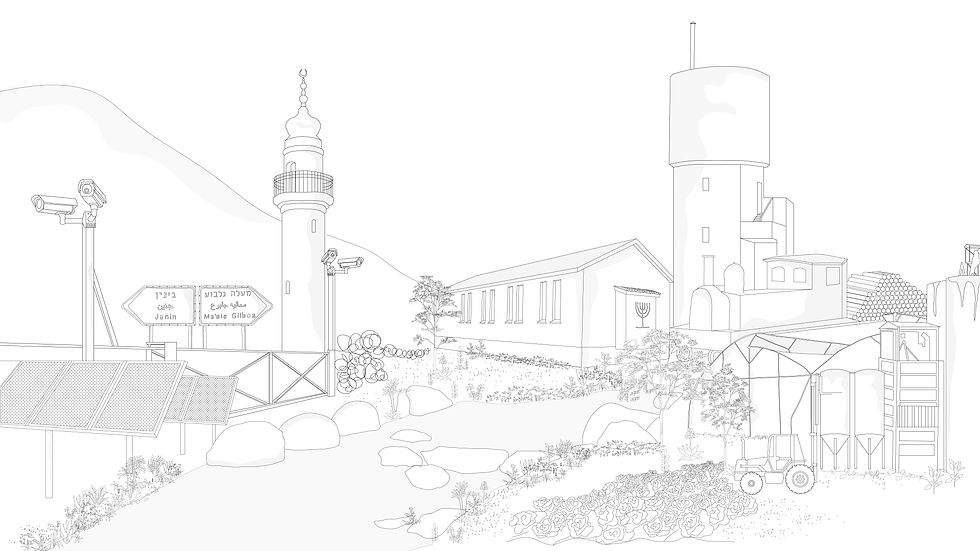

From Settlement in the Ta'anakh Region to a Future Space of Healing. The Ta'anakh region, part of the Gilboa Regional Council, lies between Afula and the outskirts of Jenin, along the Kishon Stream. This fertile area, shaped by strategic importance and ideological foundations, hosts a mix of settlements marked by social and economic disparities. Fields of Recovery maps the region as a complex rural space — layered with infrastructure, agriculture, nature, and diverse human activity. Through the lens of historical relationships and regional collaborations, the project envisions an optimistic future for a space long shaped by tension. Amid ongoing conflict and in light of upcoming supra-regional infrastructure, the project revives a dormant proposal: the establishment of a regional hospital. Reimagined as a decentralized “field-hospital” network embedded within the agricultural landscape, this model introduces a new typology of care and connectivity.

Final Project, 'Towards an Architect' Studio, guided by Architect Ifat Finkelman and Architect Deborah Pinto-Fdeda, 5th Year.

Interview on i24NEWS

I was born in Gan Ner, in the Gilboa Regional Council, into a reality in which my father served — and continues to serve — as the head of the council and as a central figure in the Labor Party. Our home was always a center of the shared life of the Gilboa — Jews and Arabs, kibbutzim and moshavim — and for conversations with regional leaders about strengthening the social fabric and the relationship with the Palestinian Authority.

From this background, I chose to engage in the creation of a space of recovery — a point of light for the future of our region and an expression of the values on which I was raised.

.jpeg)

As part of the research, an interview was also conducted with my father, Danny Atar.

This project examines ways to promote a shared future for Jews and Arabs within a single territorial space, addressing the region’s development challenges. It emphasizes integrative planning that supports economic, social, and cultural coexistence, while leveraging the potential inherent in regional diversity and in relations with the Palestinian Authority.

Can the planning and establishment of a joint medical–rehabilitation institution along the Gilboa–Jenin border serve as an effective mechanism for rebuilding trust and fostering collaboration between Israeli and Palestinian communities?

Gilboa Regional Council

The Gilboa Regional Council is located in northern Israel, in the southern part of the Jezreel Valley, between Afula to the north, Jenin to the south, Beit She’an to the east, and Megiddo to the west. It spans an area of 250,000 dunams and includes 33 communities of four types: kibbutzim, moshavim, Arab villages, and communal settlements.

The Ta'anakh Region

On the western side of the council lies the Ta'anakh region — a network of moshavim where my father was born, in the moshav of Dvora. Established in the 1950s to absorb immigration from Arab countries, the area is organized into clusters of moshavim of about 60 families each, with every family holding a “Plot A” of 5–7 dunams that includes the private house and adjacent agricultural structures.

The need to provide housing for large waves of immigration in the 1950s was expressed in the uniform design of the houses, regardless of family size: two bedrooms and a central space that served as the kitchen, dining area, and living room.

Alongside the residential unit, two agricultural structures were typically built, designed with functional simplicity: sloped roofs to prevent water penetration, ventilation openings, and proportions suited to the types of animals they housed. In some farms, fenced areas were initially built without roofing — sometimes due to budget limitations — with shelters added later. Although the farm structures varied from one moshav to another, their planning principles were similar, and several of these structures served as a foundation for my own design work.

Over the years, together with a drainage system and reservoirs built in response to repeated flooding caused by the nearby Gilboa and Kishon streams, the cultivated areas expanded into additional plots and developed into diverse and advanced agricultural crops.

Pepper cultivation

Rose greenhouse

Lettuce cultivation

Cabbage cultivation

Radish cultivation

Between Afula and Jenin

The council is defined by two relevant urban edges — Afula and Jenin — which frame its regional context.

Afula, the metropolitan center of the area, was originally planned to be a thriving city serving the surrounding agricultural communities. Although it did not develop as intended in its early years, today it fulfills its role and serves the needs of the valley and its diverse settlements.

The Emek Medical Center was first established near the Harod Spring, and in 1930 it moved to its current location in Afula. The hospital has 537 beds and serves a population of roughly half a million residents from the cities, towns, and villages across the region.

South of the Ta'anakh region lies Jenin, one of the area’s significant urban edges, located within the Palestinian Authority and separated from the Gilboa Regional Council by approximately 25 km of barrier.

The city has about 70,000 residents, with roughly 375,000 in the entire district.

Agriculture has long been — and remains — a primary source of livelihood for the people of Jenin and the surrounding villages, while the city itself has always been a vibrant commercial center, filled with shops and markets serving the wider region.

The Gilboa–Jalameh Crossing is a major border crossing between Israel and the Palestinian Authority, allowing entry into Israel for Palestinians with permits. Before the construction of the separation barrier, activity there was limited, but once formalized as an organized terminal, traffic surged from about 240 vehicles per day to roughly 3,000 per day and 7,000 on weekends, corresponding to the growing trust between the sides. As a result, Jenin developed into a significant economic hub, with businesses catering to Israeli customers and an annual activity volume reaching approximately 8 billion shekels. Since October 2023, the crossing has opened only a few times, yet its regional importance remains clear.

Relations with the Palestinian Authority

At the beginning of the 2000s, a unique relationship was formed between my father, Danny Atar, and the Governor of Jenin, Mousa Qadura. What began as humanitarian assistance developed into genuine regional cooperation. Their relationship became a model presented to leaders around the world — a model of public, economic, cultural, and regional collaboration, but above all, a model grounded in a strong personal connection.

A joint university hospital near the Jalameh Crossing emerged as an idea from this relationship, but planning disagreements and the assassination of Mousa Qadura brought the initiative to a halt. Nevertheless, significant gaps in medical care within the Palestinian Authority remain and still require a meaningful response.

״Field Hospital״

Field of Recovery — Between Fields, Toward a Shared Future

The shared vision that existed between the Governor of Jenin and my father left me with a sense of responsibility to revive the hospital’s establishment — driven by a desire to rebuild trust between the sides through mutual collaboration, and to create an innovative, cross-border model in a region defined by political and social tension.

The hospital is intended to serve as a platform for medical, social, and political healing — a place to confront crises and create new beginnings. Its purpose is to strengthen both the individual and the community, offering a better shared future for Israelis and Palestinians.

The recovery landscape is located alongside the separation barrier to enable planning advantages and the potential for future connection to the Palestinian side. Although the barrier is a physical boundary, the wider area functions as a single regional fabric. The site is composed of privately owned lands from the village of Muqeible, characterized by irregular agricultural divisions and natural constraints such as the Kishon Stream.

The site spans approximately 580 dunams of orchards, field crops, and greenhouses. The research showed that a traditional hospital model is not suited to the rural landscape, leading to the choice of a decentralized system that integrates into the valley and maintains its horizon through low-rise construction. An analysis of the gaps between Israel and the Palestinian Authority identified key medical fields requiring immediate attention, which will form the focus of the recovery landscape.

The Central Hub

The central complex includes an imaging center, a commercial center, specialist clinics, a surgical department, and a fertility unit. It serves most of the patients and enables professional collaboration between the departments of the recovery landscape, ensuring immediate access from its core to all parts of the hospital.

Children & Residents Campus

In the northern part of the recovery landscape are the residents’ complex and the pediatric department. The combination of programs highlights the unique complexity of training in this setting, which requires not only medical expertise but also cultural, social, and geopolitical understanding.

For children, the integration of the agricultural surroundings — landscape, nature, greenhouses, and a nearby stream — with their medical care creates optimal healing conditions. The rural environment and natural elements woven into the space significantly enhance the sense of recovery.

Department of Rehabilitation

The rehabilitation department is the flagship unit of the recovery landscape. It addresses a fundamental need shared by both sides — medical and psychological alike — creating a unique point of connection between them. Given the prolonged nature of the rehabilitation process, I chose to locate the department in a more secluded position within the hospital complex.

The ground-floor functions of the rehabilitation complex — such as music, cooking, and art rooms — form a direct extension of the medical process and support physical, psychological, and social recovery. These activities create shared spaces that foster connection between Palestinian and Israeli patients by overcoming linguistic and cultural differences. The therapeutic pool is also an integral part of the process, reinforcing feelings of freedom, openness, and togetherness.

On the upper floor, the focus is on healing and maximizing medical capabilities. The floor includes private and shared inpatient rooms with approximately 75 beds, alongside physicians’ and psychologists’ offices. The inpatient rooms are designed to accommodate long-term stays of weeks or months, ensuring that alongside optimal professional medical care, patients retain a strong sense of comfort and home.

The complex accommodates all rehabilitation needs, including medical programs and supportive functions that naturally connect to the open landscape surrounding the building. The inner courtyard is both secluded and integrated with the external open space, enabling physical, psychological, and social recovery to take place simultaneously.

The use of agricultural programs enables direct access to the open fields, the stream, the greenhouses, the stable, orchards, and plantations. These programs serve the guiding principle of the recovery landscape, which connects people and cultures and bridges existing divides.

Looking ahead toward our shared future, I believe that a hospital in which boundaries are softened — where nationality, language, and religion are set aside in favor of the principle of life and the most fundamental human need — can lead us toward a different and better reality.